There are more and more inspiring stories of inclusive journeys. Of people working hard to make the joy of slow travel accessible to everyone. Of people with disabilities who take on the challenge and set off. Of people without disabilities who join them to lend a hand. Of people without disabilities who walk alongside them and discover hidden treasures.

Mirko Cipollone has created some of these stories—and gone even further. For him, inclusion reaches all the way to the mountains. To rugged peaks like Velino, Camicia, and Sirente, in a region with a warm heart but still growing as a tourist destination. In one of the wildest and most stunning environments in Italy—the Apennines—where silence, emotion, and endless views run deep.

When inclusion becomes a profession

Anyone who’s done trekking knows the priceless feeling of being surrounded only by nature—of reaching a summit and looking around with nothing to block your gaze. Of feeling small before giants of stone and, at the same time, part of something bigger. Something so beautiful should be available to everyone. That’s where Appennini for All comes in.

Appennini for All is the organization Mirko created with the aim of enabling everyone to experience the mountains, walking, and trekking in an inclusive way. He forms groups of people with motor or sensory disabilities and people without disabilities who spend hours or days together sharing steps, perceptions, emotions, water, landscapes, dinners. What makes Appennini for All truly unique is that it’s a real business. You could say that inclusion is their job.

In the mountains and on the trails, together – with and without disabilities

It all began a few years ago, step by step, with awards that encouraged Mirko to bring together his passions for tourism, volunteering, organizational skills, and love for Abruzzo. In a short time, Appennini for All became a point of reference—bringing inclusive hikes out of the realm of occasional events and turning them into an always-accessible opportunity.

“It’s limiting to think that disability is something only volunteers should handle,” says Mirko. “If we approach it as a business, anyone who wants to can come to the mountains or go on a trek whenever they like.”

Indeed, every year from May to September, his groups are in the mountains 4–5 days a week with people with disabilities. Appennini for All organizes dozens of experiences, from one-day hikes to week-long adventures. They include people using joelettes (a one-wheeled wheelchair maneuvered with poles that allow travel even through rough terrain), people with visual or hearing impairments, and people without disabilities. There are also weekends for families with autistic children, who benefit enormously from contact with nature and animals.

A new frontier for local governments

For all these people, it’s the chance to live something truly special—to feel good. And for many local governments, it’s a new frontier.

“I’ll take some credit for showing people working in tourism in the Apennines that it’s possible to work with people with disabilities,” Mirko says. “Until a few years ago, it was all volunteer-based—never a job. That approach is changing. More and more organizations are entering this space, and opportunities for people with disabilities are growing.”

In the mountains of Abruzzo, some have followed his lead and opened activities like motor-powered flight experiences to people with disabilities—something few would have thought possible. But that’s the point: Mirko looks beyond the ordinary limits of what’s considered possible. He saw that expanding inclusion meant doing two things: finding resources and building networks. That’s why he spends the hard autumn and winter months in front of a computer, working on funding applications that make inclusive hikes feasible.

Walking with sunset concerts

Thanks to one such grant from two years ago, a new camp is about to launch—in collaboration with NoisyVision ETS—exclusively for youth aged 15 to 20 with and without visual and hearing disabilities. For just 50 euros, they’ll spend 5 days walking together, picnicking outdoors, and participating in traditional cooking workshops.

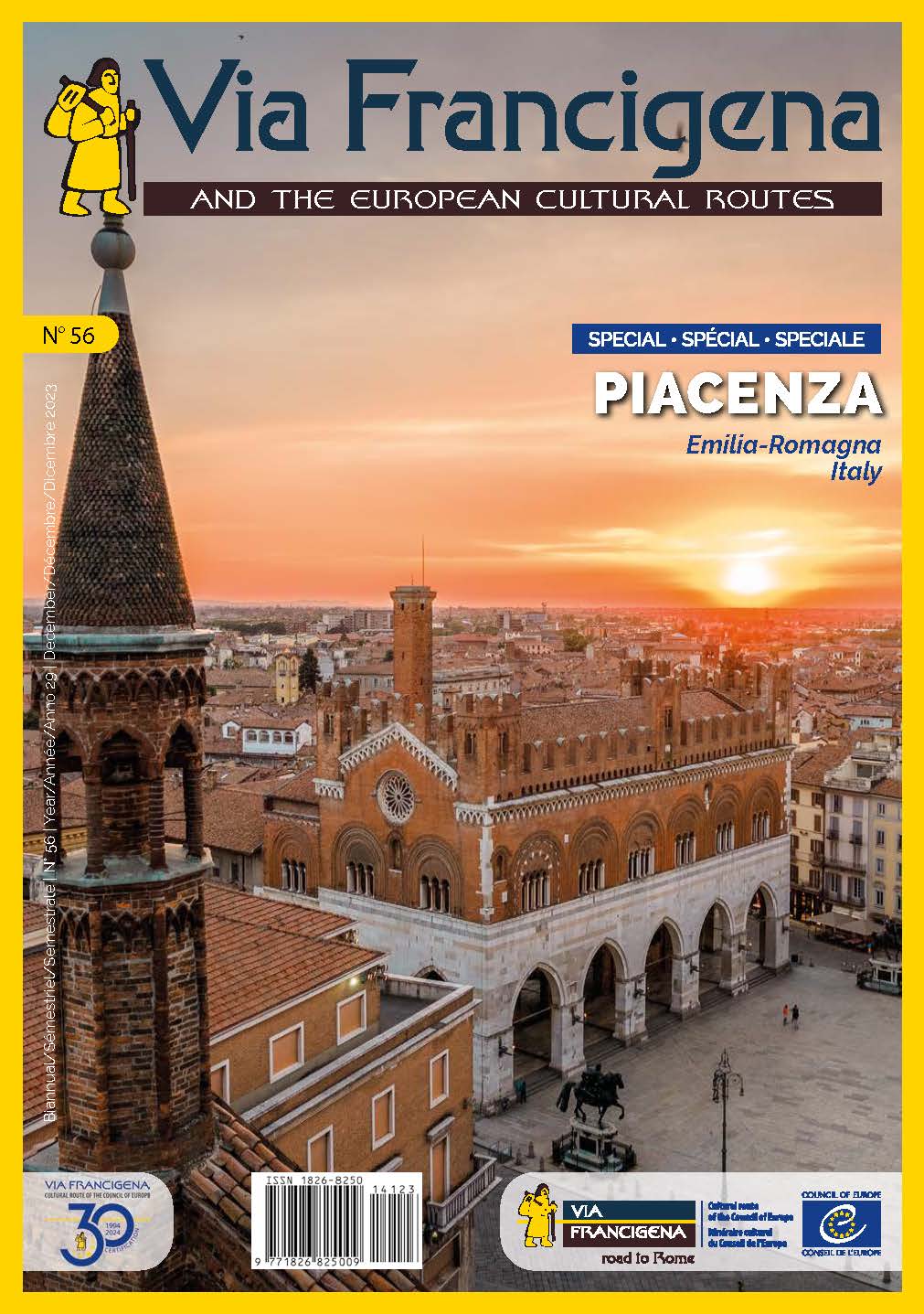

In July, the Cammino di Celestino (Celestine Way), led by the Maiella National Park, will offer inclusive activities like dining in the dark, open-air reading, and sunset concerts alongside the morning trail stages. A multifaceted experience that Mirko hopes to bring to other pilgrimage routes—and why not, to the Via Francigena too.

“Some parts are already accessible for people with motor disabilities, but we could do even more—organize a few inclusive, experiential days that expand horizons for everyone. There’s no shortage of ‘material’ to work with, considering the cultural and traditional wealth of the Francigena.”

For institutions like national parks, accessible tourism is still relatively new. But thanks to Mirko’s gift for connection, collaborative experiences are emerging. As with the Via Francigena, there’s a growing awareness that networking can lead to mutual growth. Together with PNALM (Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park), they produced a report on tourism accessibility, and phase two will launch soon. Meanwhile, with the Unione dei Comuni Marsicani, there’s an ongoing project to make 10% of the newly built 1000 km of cycle paths accessible.

Connection is the winning strategy

“To make something truly work, you always have to build connections between public institutions, private businesses, and nonprofits,” Mirko says. “Only when they work hand in hand can real planning happen. I’m a big believer in networks—where everyone plays their role and lets others bring their expertise. I often ask administrations to connect me with local associations because no one knows the territory like they do, and those working for community well-being should be empowered.”

Without that web of support, inclusive projects wouldn’t be economically viable—and certainly wouldn’t be rich enough to include things like sunset concerts or handmade pasta workshops that engage all the senses.

One of the biggest challenges remains accommodation. In the Apennines (and elsewhere), many places are family-run and not accessible to people with motor disabilities. It’s a reality unlikely to change without specific incentives.

Meanwhile, Mirko’s projects keep moving at full speed. And even though he’s made inclusive tourism his profession, his spirit is still that of the young volunteer who believes in the definition of social tourism: all people, regardless of physical or economic condition, have the right to a vacation. And even though he now has a paid team of professionals, in mid-June they’ll climb Mount Camicia as volunteers—supporting someone who asked for help to fulfill a dream: to return to the summit, even now in a wheelchair. At 2,500 meters. “It’s tough,” he says, “but I’ve got a great team.” And this group, too, will be mixed.

“There are never only people with disabilities: the benefits of doing things together are for everyone. There aren’t two separate worlds—there’s just one.”